Keeping Families In Touch Through A Bus Ride To Jail

For incarcerated moms, even a monthly visit from their kids can make all the difference

Holly Krig has long been something of an activist. She worked as a union organizer, and as a community-based organizer on housing issues in and around Chicago. “Very often, the people I was working with most were moms who were facing housing insecurity or eviction,” Krig recalls. “They were also often impacted by incarceration in some way, either because a partner, a father, or another caregiver was incarcerated, or the mom had been criminalized in such a way that she was denied access to housing support.”

Then, five years ago, Krig became a mom herself. “That was one of the things that got me thinking more and more about incarceration and mothers, and I started to learn more about the reality of incarceration for women,” she told Good Turns recently.

One harsh reality stood out to her: From the south and west sides of Chicago, where most of the people she encountered in her work were from, to the Decatur Correctional Center and the nearby Logan Correctional Center was a distance of some 180 miles — no easy trip for a kid from a poor neighborhood whose mom was in jail.

“When moms are incarcerated, kids are statistically more likely to go into foster care than kids whose fathers are incarcerated,” Krig says. For that and other reasons, mother get fewer visits from their kids while in jail or prison than fathers do. “The reality is, it’s just so expensive,” Krig says. “You can’t bring food or beverages into the visiting room, so you have to rely on expensive vending machines to spend a day with your loved one, and you’re going to spend a couple of hundred dollars on a typical trip.”

“Some moms are going to be there for decades. Some are there for a couple of years, but it’s still a really long time to be separated from your child.”

Lutheran Social Services had run a bus from Chicago to the jails every month with state funding, but that service was cut several years ago when the state entered a prolonged budget crisis from which it has yet to emerge. So in 2015 Krig and Alexis Mansfield, an attorney at Chicago legal-aid firm Cabrini Green, decided to do something about it. To support a new bus program, they brought together a coalition of Chicago-area advocacy groups including the Chicago Legal Advocacy for Incarcerated Mothers program (CLAIM) of Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a community organization called Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration (where Krig is Director of Organizing), and Nehemiah Trinity Rising, a prison ministry and non-profit devoted to “building peace” that operates out of Trinity United Church on Chicago’s South Side, a church that has long been associated with former President Barack Obama and the rapper Common.

The new bus program, known as the Reunification Ride, launched in early 2016, with the help of thousands of dollars in crowdfunding, and has been bringing kids to see their moms in Decatur and Logan every month since then — with two trips in May for Mother’s Day and two in December for the holidays.

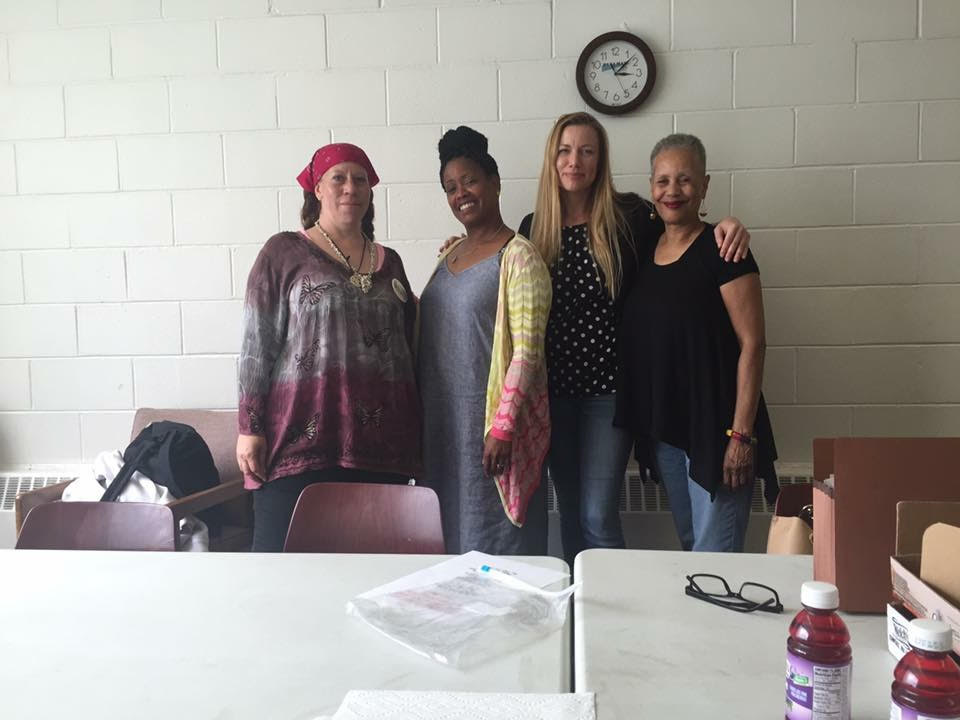

Just raising the money was only the beginning of the journey. Mansfield and Krig (second from right, above, with Reunification Ride partners from left to right: Monica Cosby of Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, Colette Payne of Cabrini Green Legal Aid, and Olivia Chase of Nehemiah Trinity Rising) had to locate an insurance broker, negotiate bus prices, talk with caregivers and find out who hadn’t had a visit for a long time, and then coordinate with the correctional centers to insure they would allow the visits to continue to happen.

The buses are loaded at 7:00 am for the 180-mile trip. It takes half an hour or sometimes more to get everyone through prison security, Krig says, but once they do, visits take place not in small visitation rooms but in an auditorium. “It’s a larger open space where people can have time together as a family, and kids can play together and run around,” Krig says, “The prisons allow us to bring craft supplies and desserts, and they provide us with lunch. We eat the same food the women eat every day. So caregivers who don’t have a lot of money don’t have to worry about spending money on vending machines.”

“It’s an opportunity for the kids to be together, too. Some moms have very long sentences. Some moms are going to be there for decades. Some are there for a couple of years, but it’s still a really long time to be separated from your child. Some of the kids aleady know one another from having ridden the bus. They’ve got a mutually supportive community of kids and caregivers, which we’ve been encouraging.”

Though the bus program works to keep people in touch, Krig says there is far more work to be done. “The reality is that incarceration disproportionately and overwhelmingly impacts black women and black mothers in poor communities,” she says. “So we talk about what kind of changes we need to make in terms of policy. There’s an unwillingness to make the decisions that might not be politically popular in order to insure we’re properly funding communities. The failure to do so is measured by seeing increased rates of incarceration, which then also costs more money. It would be much cheaper to subsidize housing for women in the community and support other needs than to incarcerate them.”

Regardless of how much work we as a society have left to do, the work Krig is doing is at least easing part of the burden and keeping the connection going for families who might otherwise collapse under the weight. That’s the kind of good turn that’s hard to find no matter how far you travel.

Posted May 26, 2017