Befriending Latin America—And Potatoes

Sometimes, doing good means not eating so well

As a high school junior, Jeremy Engels had wanted to study abroad. His plan turned out to be impractical, but when a speaker from an organization called Amigos de de las Américas visited his school to describe their programs—which matches teenaged volunteers with communities in Latin America—he knew what he wanted to do.

“My first year I went to Costa Rica, to a small little tiny village of 100 people,” he says. “You’re paired with one other American youth. So it was the two of us living with host families, with no other supervision. There’s one supervisor that came around once a week to make sure we weren’t dead and to check in on the project, but effectively it was the two of us in the community alone. It definitely took some getting used to. My Spanish wasn’t incredibly strong before I went there, but after two months of speaking nothing but Spanish it improved quite a bit.”

One of the unique things about the Amigos experience is that the volunteers work with the communities to determine the right projects to pursue. “The project that we came up with alongside the community was fixing the surrounding areas of the village church,” Engels told Good Turns. “The supervisor helped us with the first meeting, because we were two little 16-year-olds, we were very nervous. But then it was really just up to us to go talk to people. It was really the community who decided upon the project.”

“It was this muddy grass, and Costa Rica is very tropical, so when it rained it got very muddy and sort of disgusting, and for the villagers wearing their Sunday best that’s not a good combination,” says Engels, now an engineering major at UCLA. “We organized the community and they all got their farming tools and we ordered gravel, and with the community we removed all the grass and put gravel in its place and installed a drainage system and that was it.”

After Engels returned from Costa Rica, he was so taken with the program that he decided to become a trainer at the San Francisco chapter, to help train the next year’s participants in the program. “But at some point, when I was thinking about my next summer, I realized there was really no place I’d rather be than in Latin America again,” he says.

“I started keeping a count of how many potatoes I ate over the summer. Sometimes I still miss those.”

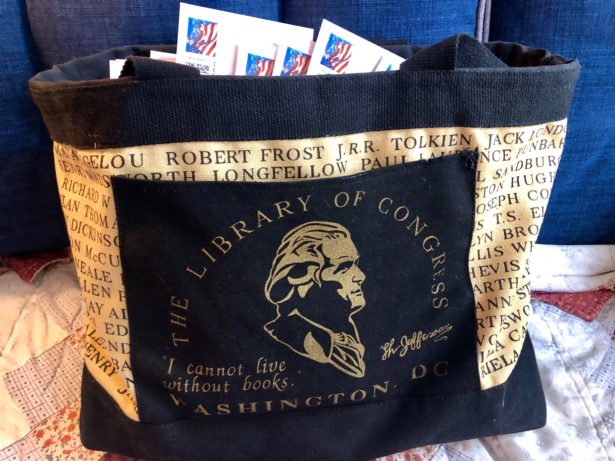

This time, Engels was assigned to a village in Ecuador called Larcapungo—Gate of the Fog, in the indigenous Quechua language—at an elevation of 13,000 feet in the Andes (pictured above). There, the community wanted to do more than just launch a project, so they decided to try to create a microcredit lending facility. “I think a lot of community members felt, We can always make an alpaca farm, we have the ability to do that, that’s not such a big problem. But if we could start a bank and then other members of the community can access credit to start their own businesses—it’s almost being more Amigos-y than Amigos itself.”

This project faced a whole different set of challenges. The Amigos organization was at first uncomfortable with the idea of funding a local lending organization, and community members were uncomfortable with the idea of some of the agreements that the organization was seeking. “When we told some of the community members that we’ll have to have a lawyer sign these, they were outraged. They said, ‘We don’t want any of this white people magic, this is our community, we handle things.’ So that created a bit of tension,” Engels recalls. Everything got worked out in the end, and Engels reports that the lending facility is still operating, almost a year later.

“I was in each of those countries for eight weeks, so basically my whole summer,” Engels says. “I felt very fortunate that I was able to participate in that. It was very eye-opening. Through the focus on sustainability and making sure that the project is the community’s project, it’s not the Americans walking in there and building something. Clearly I enjoyed it, and I believe in the organization, because even after I came back from Ecuador I was involved with the San Francisco chapter again, even with no intention of going to Latin America a third time. I was the associate training director of the San Francisco chapter, and I’m still very much in contact with the participants that I oversaw and the people I met in Ecuador and Costa Rica, and still pretty good friends with the people I knew, and my partner in Ecuador, we’re still very much best friends.”

And those potatoes?

“Yeah, so, potatoes,” Engels says, sounding almost—but not quite—wistful. “In Ecuador, three meals a day, it was this potato soup. If you can imagine the potato, it was just harvested from the field, it still has a little dirt on it, but it’s fine, you sort of wipe it off and smear it a little bit but it’s pretty clean. You cut it in half, and then you toss it in some mildly warm water, and there’s your soup.”

“Maybe you throw some peas in, but that’s your soup that you have for every meal,” Engels says. Not the soup course, he stresses, the entire meal. “It was really just potato soup for three meals a day. I lost 17 pounds. I was already pretty skinny, so my mom wasn’t happy with how skinny I was when I came back home.”

“I started keeping a count of how many potatoes I ate over the summer and I think I got up to 700 or so over those two months. At some point I went to the village and bought some oil and made French Fries, and they were like, Oh wow, que bien. And they put some mayonnaise on them that they had lying around. Then they said, ‘Oh, so tomorrow we’re going to harvest potatoes, can you just make us French Fries for dinner?’ So I was in this little kitchen hut cooking French Fries for maybe five hours. Sometimes I still miss those,” Engels says with a wry smile. “Just with a hint of dirt and some questionable mayonnaise.”

(Photo by Jeremy Engels)

Posted April 6, 2018